What’s certain about (caribou) death and taxes?

Posted on

Future Energy Systems HQP Zhanji Zhang focused his Masters on using economics to try to save the caribou, and the answer may lie in avoiding taxes

A caribou wandering through a northern Alberta forest steps out into a long, straight clearing. The clearing is kilometres long with edges that are very clearly defined. It’s not naturally-occurring, but it also isn’t an unusual sight –– just one of many lines in an orderly grid of north-south and east-west corridors that slice through the boreal forest. It is the result of human efforts to extract fossil fuel resources. Once exposed in that clearing, the caribou is easily spotted – and easy prey – for any wolves that may be watching from a distance.

These corridors –– termed ‘linear features’ by industry –– contain the roads, pipelines, and seismic lines that oil sands operations rely on to function. But when operations cease in an area, they remain on the landscape, and because they are so wide, the chances of them refilling with forest naturally –– of ‘self-recovering’ –– are very low.

Land disturbances, like an oil pipeline, can stretch for kilometres and drastically affect the landscape, and caribou habitats.

Land disturbances, like an oil pipeline, can stretch for kilometres and drastically affect the landscape, and caribou habitats.

With fewer places to hide and easier access for predators, caribou populations are declining and now classed as threatened, and pressure is increasing for energy producers to refill these unused corridors. But how can energy producers be effectively incentivized to undertake reclamation operations for the sake of the caribou?

Recent Future Energy Systems Masters graduate Zhanji Zhang assessed the options, under the supervision of FES researcher Vic Adamowicz and Research Associate Grant Hauer, in the Department of Resource Economics and Environmental Sociology.

“We know we need to reclaim these lines as early as we can to support caribou habitats,” Zhanji explains. “The question is how to incentivize firms to want to do so, without the resistance that policy often meets. Especially when new operations start, and inherit these legacy features, companies feel like they’re being targeted unfairly for things that aren’t their responsibility.”

The solution, Zhanji believes, is to approach the problem with a tax-based carrot-and-stick mindset, making the disturbances expensive for operators to live with –– but offering competitive advantages when they’re reclaimed.

Tax carrots and sticks

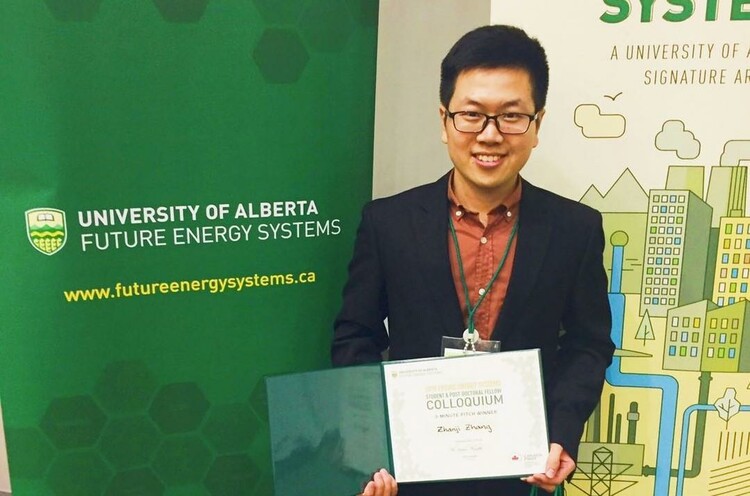

Zhanji presents his work at the Future Energy Systems Research Colloquium in 2019.

Zhanji presents his work at the Future Energy Systems Research Colloquium in 2019.

Theoretically, induced land reclamation by operating firms can be optimized by taxes, dependent on the scale of the land damage that firms have on the land –– in other words, taxing companies for having legacy corridors on their sites. The problem, Zhanji points out, is that heightened taxes can adversely affect industries and regional economies. In fact, in the face of heightened taxes, firms might simply decide not to stay “in the game”, even when it makes economic sense for the firms to operate.

“Companies have the option of ceasing operations – they can make money by going to places without taxes for linear disturbances, or simply file for bankruptcy,” Zhanji explains. “We need them to want to play the game, and that can be done much more effectively using a tax-refund model.”

While taxation models only charge penalties for unreclaimed linear features within an operator’s land, a tax-refund approach creates an opportunity for the company to recoup their losses through higher tax credits based on their energy production –– in Zhanji’s proposal, applied per barrel of bitumen produced.

“Firms may be taxed for the damages to the land they operate on, which acts as a stick. But they also know if they produce more energy on that land, then they’ll receive higher refunds, a carrot,” he says.

Higher return for greater energy production creates an incentive for operators to stay in the game, and the possibility of eventually reducing their tax burdens by reclaiming linear disturbances creates the opportunity for even greater future revenues –– or a reduction in tax costs later in the life of a site, when its productivity and profitability might decline.

In Zhanji’s proposal, the stick and the carrot would actually balance out to net zero for all firms as a whole –– the total refunds that all firms would receive for their production of energy would offset the total taxes that they pay for linear features.

Zhanji came to this solution through a mix of simulation and optimization that considered the totality of the small in-situ oil producers in the area in question –– 317 steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) projects in the Alberta oilsands. His simulations had to account for sector-wide behaviours and relationships between the different companies, assuming that all operators understood each others’ operations, and that their behaviours would influence each other.

“There’s interconnections, and we have to consider as many of them as we can to make more accurate predictions,” Zhanji says. “For example, we assume that if one operator will gain a profitability advantage by reclaiming legacy features, competitors will recognize this and wish to obtain the same advantage.”

Simulating these sorts of interconnections is time consuming and intricate, but Zhanji believes the resulting recommendations are much more realistic. That sort of realism is exactly what brought him to the University of Alberta.

A World of Economics

A convincing argument: Zhanji brought home first place for his three minute thesis on tax-refund schemes to save the caribou.

A convincing argument: Zhanji brought home first place for his three minute thesis on tax-refund schemes to save the caribou.

When Zhanji came to Canada from his home in China, he had already been studying economics for years. As an undergrad student he knew it would be his path, but he worried his lack of a serious mathematics background would hold him back. Rather than pure economics, he therefore decided to pursue the more cultural, environmental, and development side of the field.

“I like the applied work on economics, so I’m happy I chose this. I could apply many theories into environmental and energy issues, and it was more realistic for me.” he laughs.

His first Masters in environmental economics was completed at Renmin University of China, with his thesis considering the mechanisms and interaction between economic growth and environmental quality. “It’s a macro-level approach, using data from cities,” he explains.

By contrast, Zhanji considers his FES research to be micro-level. “My work here was focused on the oil sands, with data on specific firms. There’s many more details you can consider when you narrow in like that. You can control more, so it’s more accurate. Both types of research are interesting and useful.”

Since graduating, Zhanji has turned his attention to yet another type of resource economics project: he is working with FES researchers Marty Luckert, Feng Qiu, and Grant Hauer to explore the question of refining agricultural and forestry residues into useful products like biofuels.

“An essential question is: where are the best places to process biofuel feedstocks, taking account of uncertainty and other constraints?” he says. “It’s an optimization problem. The industry currently doesn't have the information needed to optimize their resources, so this is what we’re currently trying to do.”

This work requires him to assess the potential profitability of thousands of potential sites for biomass refining plants –– or biorefineries. Many factors are involved: the price of electricity and subsidies on the revenue side, as well as costs from the transportation required and plant operations. This also includes the question of whether the suppliers –– the farmers whose residues would be turned into fuel –– sell the material at fair price given other usage of residues, or if the price of the waste is affected by the existence of the plant.

“It’s a different focus and I’m learning new computational skills from Grant, which are very unfamiliar to me. It’s a great opportunity that I’m very thankful for,” he says. “There are many different details to consider.”

Valuations in the details

Zhanji with his Masters supervisor, Dr.Vic Adamowicz.

Zhanji with his Masters supervisor, Dr.Vic Adamowicz.

In all of the research that he’s been part of, Zhanji and his supervisors all knew that small details can have huge impacts. For instance, the fact that linear disturbances have put caribou at risk is significant –– if the species in danger were different, the appetite for tax policy interventions might not exist.

Zhanji observes, “In China, it’s pandas. We would do a lot to protect panda ecosystems, because they’re a high value animal for us. In Canada, the caribou is of high value.”

In previous studies, estimates of Albertans’ resolve to ensure caribou survival have been quantified to a dollar amount, he explains, which can then put a price on the ‘cost’ of land damage based on the harm it does to those caribou. The land damage linked to a one kilometre stretch of a wide linear feature can therefore be priced at $1400-$1600 CDN.

Being able to identify and use these sorts of valuations is critical to informing accurate decisions and models, which must account for all facets of human behaviour, including how much people favour various ideas and things.

To Zhanji, it’s also one of the things he values most in resource economics.

“Every day, people make choices about what they value. Economics is about looking at how those decisions interact, and the effects they have,” he says. “It’s a different way of looking at the world, and I think it’s fascinating.”

Zhanji cannot see himself leaving the world of economics; he has decided to accept the offer from the University of Minnesota, and he hopes to begin in the fall to pursue a PhD position in the Department of Applied Economics.

“I would love to be a professor or researcher, and study these interactions even more,” he says. “The deeper you dive into the sea, the deeper you feel about it.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To learn more about Zhanji’s Masters project, Economic Analysis of Reclamation Technologies and Policy Options, click here.

To read about Zhanji’s current work in Investment Decisions and Policy Analysis, click here.

To read more about other FES HQP, click here.

To get notified of new research stories, subscribe to the FES newsletter.