Spinning up electric buses

Posted on

Flywheels could charge City of Edmonton electric buses faster, changing the way sustainable transit is powered in Canada and around the world

It’s a sunny spring day outside a University of Alberta graduate student office, but mechanical engineer Muhammad Saad Arshad sits at his computer, poring over bus schedules and transit system logistics. He’s not planning a commute, he’s working on an idea that might help form the basis of Edmonton’s innovative electric bus fleet initiative.

It’s a timely project. The number of electric vehicles on the road continues to rise every year according to the International Energy Agency, with estimates currently predicting over 200 million electric vehicles by 2030 – the same year that the City of Edmonton plans to reach 100% electric buses in its fleet. The city has already begun working towards this visionary goal with the largest purchase of electric buses in Canadian history.

But implementing new technologies means developing new systems to support them. That begins with understanding the function of the current system, and ways to drop in new technologies that could change how it functions. Saad is ready to contribute to that understanding.

Real challenges, real data

Saad only recently started work on this project, but he and his supervisor – Future Energy Systems Principal Investigator Dr. Pierre Mertiny – have already achieved some important milestones.

“We submitted our proposal to the Sustainability Scholars program and were accepted, which is really helpful,” he explains. The program is a partnership between the University of Alberta Sustainability Council and the City of Edmonton. This means Saad can access actual, real-time data from the Edmonton Transit System (ETS), including some proprietary information not available to the public. “Otherwise, we’d be using virtual data, or only public info, which isn’t ideal."

One of the key issues Saad is addressing through his analysis is an often-cited drawback of electric vehicles: slow, cumbersome charging requirements. Traditional charging methods could play havoc with the ETS system, requiring more downtime per vehicle and therefore more buses in the fleet. Right now, charging an electric bus for a day of driving can take hours, though that might change if Saad determines it could be practical to implement an energy storage technology that the Mertiny group has been developing for years: flywheels.

Spinning power

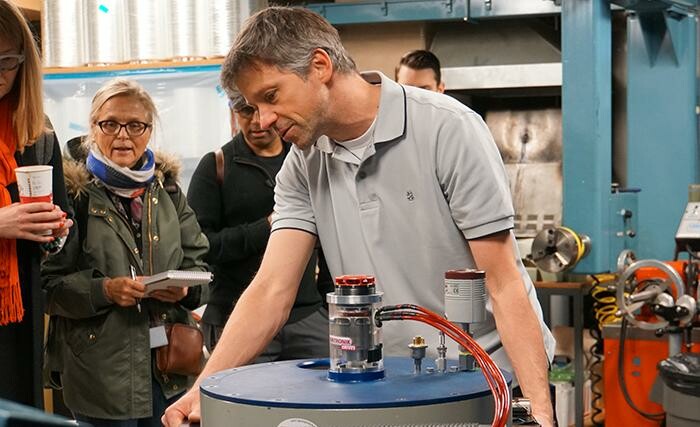

Principal Investigator Pierre Mertiny with a flywheel test unit.

Energy can’t be created or destroyed, but it can be stored. Not all storage options are built equal: most people are familiar with chemical-based solutions like the lithium batteries found in cell phones, which store energy in the form of chemical reactions between two components that release energy when they interact. In flywheels, energy is stored kinetically –– like a spinning top –– meaning no reactions take place and no components are used up.

“It’s more sustainable than chemical batteries,” Saad continues. “They have longer lifespans. Flywheels can last decades without much wear and tear.” With increasing concern over discarded battery waste creeping into headlines the world over, this is a huge environmental benefit of the technology.

The basic component of a flywheel is a ‘rotor’ –– a spinning mass –– that is enclosed in a vacuum and attached to an ‘electrical machine’. When energy is fed into the flywheel, the electrical machine acts as a motor, spinning the rotor, and because it spins in a vacuum with minimum friction, it can keep spinning for extended periods of time. When it’s time for the energy to be used –– for instance, to charge an electric bus –– the electrical machine can be connected to the rotor and acts like a generator, expelling the kinetic energy.

Within a city, a properly planned system of these flywheels could be choreographed to draw power from the grid over time, helping avoid peak demands and thus delivering power in an orderly and balanced way. When all the buses return to the depot at night and plug in, a bank of flywheels that had spun up over the course of the day could charge them, instead of the grid suddenly being expected to do the work. And because they are not limited by the capacity of the city’s electrical grid, flywheels could charge buses faster –– perhaps in as little as a few minutes. This speed opens even more possibilities for increased efficiency.

“Beyond charging at the bus depot at the end of the day, we can also look at on-route charging,” Saad adds. With buses often sitting at stops for minutes at a time to maintain consistent schedules, on-the-go charging from flywheels could keep them powered up all day, further simplifying bus route planning and scheduling. Even better, the technology is drop-in, meaning it’ll work with the electric buses that already exist.

Changing lanes

Saad presents at the 2019 Student and Post-Doctoral Fellow Colloquium.

Only a year ago, Saad was in his home country of Pakistan considering career paths. A recent graduate of mechanical engineering, he had moved into the field of project management, spending two years working in industry before Shell Pakistan offered him a more front-facing position.

“I enjoyed my job but when I looked around it seemed like everyone had more management background than me –– I had none,” he laughs. Saad saw the value of returning to school, and was considering an MBA when a friend pointed him to an opportunity half a world away: a Masters in Engineering Management at the University of Alberta.

“My project is more focused on systems analysis and implementation,” Saad explains. “I don’t work on optimizing the flywheels myself. My labmates are the ones who make sure we’re using the best materials, and understanding how they work before we use them for the buses.”

So far it’s working out wonderfully, with his colleagues in the Mertiny group designing and producing flywheels from different materials, testing how they perform, how long they last, how they might perform when they fail –– generally trying to make them better.

Saad’s days focus more on system planning, which is why he’s spending a sunny spring day (a prized occasion in notoriously-cold Edmonton) poring over schedules and routes. He needs to deeply understand the implications of including flywheels in the current ETS infrastructure, and ultimately model the system to see how different options might work.

Any chance of risk associated with a change in technology must also be assessed, and with a sustainability-minded project like this, there is also the environmental impact to evaluate. These are all critical factors to address with any new large-scale project, especially when it hinges on an innovative technology that’s yet to penetrate the market. Untested technologies can bring concerns of cost, maintenance, managerial strategy, and general feasibility into play. Saad aims to provide the City of Edmonton with the information necessary to truly consider flywheels as part of the electric bus initiative.

Saving the whole world

It was during his time at Shell Pakistan that Saad realized the importance of developing green technologies.

“Walking down the street in Pakistan, there’s so much pollution, it’s not like here. Sustainability is the way to go forward,” he asserts.

Coming to Canada to get involved in Future Energy Systems simply made sense. Saad explains, “In my mind, new technology development must start with the developed world, where the infrastructure is in place and the research can be done more efficiently.” Good work travels far, and Saad is dedicated to contributing directly to that process.

The application of flywheels for electric vehicle charging is not a concept trapped in the distant future. Saad and the Mertiny group as a whole are determined to prove that not only is it feasible in the short term, it’s also smarter, faster, and all-around better.

“If the technology can mature here, it can spread, and will eventually go everywhere,” Saad says. Progress is expensive, but he believes that’s true for both newer, green technologies and traditional ones. “So, why not implement the green option?”

If it can be made reasonable and affordable in Canada, he hopes more countries will choose to adopt environmentally responsible options, and that everyone will benefit.

“We have to save the whole world,” Saad concludes. “We can’t just save parts.”

To follow the progress of this and other Future Energy Systems projects, subscribe for our newsletter.

To learn more about the project Distributed Energy Storage, click here.

To read stories about other Future Energy Systems graduate students, click here.

2019/08/02: This story was updated to reflect the nature of the Sustainability Scholars program, a venture of the University of Alberta Sustainability Council and the City of Edmonton. For more information, click here.