Don’t underrate undergraduate research

Posted on

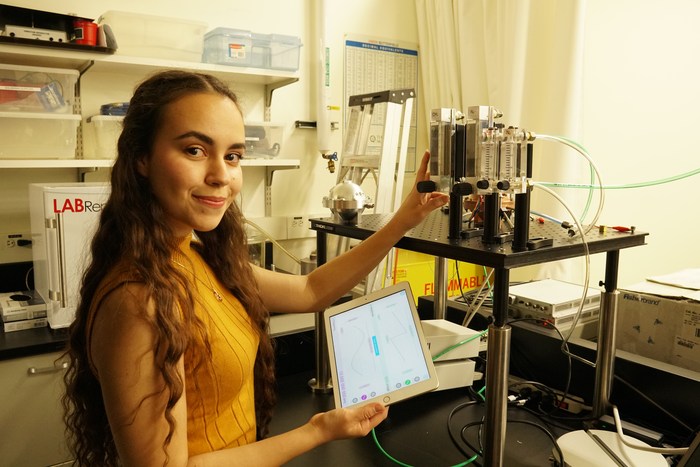

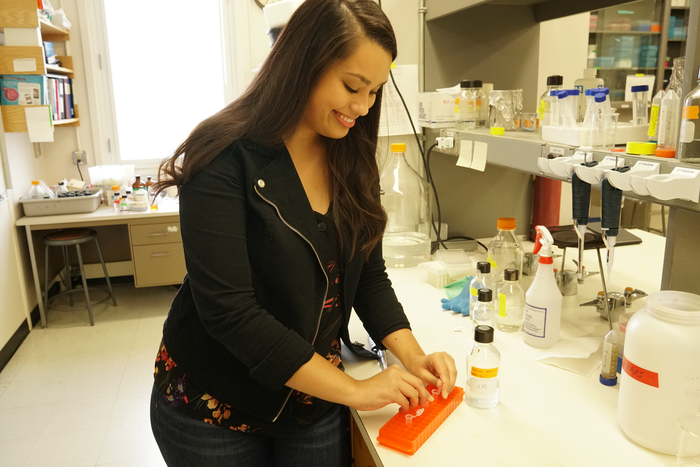

Mariah Hermary and Sofia Arango Arroyave, two recipients of FES URI scholarships to support diversity in research

Inclusivity at every level is vital in pushing research forward

To Sofia Arango Arroyave and Mariah Hermary, higher education should feel like a community of people coming together from all walks of life and all parts of the world. As undergraduate students and minority women working in the field of science research, they have a unique and important perspective on the situation. But despite the strides being made in pursuit of equity, diversity and inclusion within academia, women –– and especially minority women –– remain underrepresented in the disciplines of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Sofia and Mariah are undaunted by those statistics, and through their research are becoming part of a change that they view as essential not just because it is right, but because it will improve the quality of research in years to come. The University of Alberta and Future Energy Systems agree.

In 2011, the University launched its Undergraduate Research Initiative (URI) to create an environment in which any interested undergrad student can engage in research and get a true hands-on experience of the world of academia. In 2019 Future Energy Systems sponsored the creation of a new URI stipend, which is aimed specifically at supporting women, visible minorities, indigenous persons and persons with disabilities to pursue their interests in energy-related research.

Two recipients of this inaugural round were Sofia, working in the lab of Dr. Alkiviathes Meldrum, and Mariah, working in the labs of Dr. Dominic Sauvageau and Dr. Lisa Stein.

Young Researchers, High Energy

Sitting across a table from each other at the end of a busy summer that had been filled with full-time research, Sofia and Mariah find they have much in common.

“I had a great time in the lab this summer. It was such a welcoming experience,” Sofia says.

“It’s nice to feel trusted to handle your own project,” Mariah adds. “And to show what you can do.”

Both Biological Sciences students are in the final year of their undergraduate degrees. Along the way, it was the acceptance of inspiring professors that ushered them into the world of research. Now researchers themselves, well enmeshed in their labs, they’re making real contributions to their respective fields through two projects that examine the problem of methane emissions from industrial processes.

Sofia is working on a new technology for detecting non-reactive greenhouse gas emissions like methane using super reflective infrared mirrors in a more cost-efficient and higher resolution sensor. Despite her biology background, Sofia found her work in a physics lab.

“It was all because of a schedule mix-up,” she explains with a laugh. “I ended up in the wrong class and asked Dr. Meldrum for help a lot. I guess I impressed him, because at the end of the class, he told me about this opportunity.” Now, Sofia is thankful for the mistake, and grateful for the close support of her supervisor and her mentor in the lab, PhD student William Morrish. “They’ve both been so open and available, it’s been a great learning experience.”

Mariah is studying how methane-eating bacteria produce ‘vesicles’ –– lipid-enclosed sacks –– which might have implications for their use in carbon capture and methane conversions. She’s been a part of Dr. Stein’s lab since the previous school year, when Stein accepted her for an independent research project. “I’m really glad Lisa agreed to take me in.”

Beginning her work under the mentorship of PhD student Phillip Sun, Mariah initially discovered the formation of the vesicles that she now studies. She cites the lab community and her supervisor as encouraging her to continue.

“All the grad students in the lab have been really helpful, and Lisa is such a great source of knowledge, every time I talk to her.”

Sofia also credits her supervisor and labmates for encouraging her to continue, “It’s intimidating to start, you don’t know what it’s going to look like. By the end of the summer, it’s a different story –– the lab feels more like a community than the university does.”

While both young women are appreciative of the support they receive in their current labs, they can both recall very different experiences related to research.

Room to Research

While both women count Canada as home, they are also proud of their roots. Sofia was born in Colombia, her family immigrating to Canada when she was 10. “I learned English in Toronto where we lived. I came to Edmonton after.” There isn’t a large Colombian population in the city, but Sofia says it’s nice to meet other Latin Americans when she can. “It’s just a feeling of shared culture.”

Mariah was born in Canada, but part of her family hails from Guyana and Trinidad. “I’m biracial, and there’s not a lot of Guyanese or Trinidadian people here,” she observes. “But Canada and especially the university is so multicultural, all the different people together, the foods, it’s great.” She points out that it’s much easier to feel at home when you’re not the only one who might look ‘different’.

“I’m actually proud to be someone not from here, and doing as well as everyone else,” Sofia adds. “I feel like I have this whole other aspect to share.”

Mariah concurs, “I definitely agree. I like that everyone gets to bring their culture and point of view into it.”

But being women in STEM has not always been as enriching.

“I only came to the U of A halfway through my degree. At my old school, I did notice a bias against young women –– that science isn’t for them,” Mariah shares. In her experience, it was more common to experience prejudice from older generations, and often through off-hand remarks. “People would say, ‘Even a girl can understand’, which is frustrating.”

Sofia adds: “Even in our age group, I would explain something from class to a guy and he would go check with the professor –– but he wouldn’t if another guy explained it.”

Confronting this bias led both students to adopt a balancing act familiar to many women.

“You don’t want to come off as too authoritative,” Sofia explains, “because it reads as ‘bossy’ from a woman, and it might lead to your opinion or comments being dismissed.”

Both believe the presence of more women in the lab can have a big impact on these perceptions.

“It can be easier to immediately relate to another woman,” Mariah says.

“I feel like it’s less intimidating and you can talk more easily, when the group is more equal,” Sofia agrees.

Equality and Diversity

According to Statistics Canada (StatsCan), there’s been notable progress in women’s equality in higher education. In 2016, for the first time ever, more women aged 25-34 graduated with doctorates than men, across all fields. However, when restricted to fields like engineering, math, life and physical sciences –– all fitting under the STEM classification –– women were noticeably underrepresented compared to men. Clearly, this issue remains relevant.

Knowledge does not change depending on who discovers it. However, sometimes knowledge can be more easily found when a diverse group of people, sharing different experiences and expertise collaborate in its pursuit. New doors can be opened, unconsidered possibilities pursued, and creative thinking applied to problems that previously seemed intractable.

Both Mariah and Sofia know that good research requires every possible advantage to succeed.

“When you’re doing research, sometimes it feels like you’re 3 ahead, then 2 behind,” Mariah says.

“It’s adjustments, figuring out what doesn’t go wrong, lots of trial and error,” Sofia adds. “Everything branches, and the more minds involved, the more branches can grow.”

Everyone must play a role in creating an environment that sustains that growth. More diversity must be fostered in labs through programs like the FES URI stipend, helping young researchers from diverse backgrounds pursue research careers with confidence.

“When you like science, as a girl, it’s like, wow, that’s pretty rare,” Mariah explains. She says what follows is sometimes a push towards nursing –– an acceptably ‘pink-collar job’ that StatsCan finds currently has a 94 percent female graduation rate.

Nursing is an absolutely vital calling for society, but Mariah points out that it shouldn’t be the only acceptable choice for women interested in STEM. But in STEM paths typically more populated by males, she’s encountered uncomfortable situations: “Your mistakes feel more showcased. Boys don’t get as much negative attention when they’re wrong or make mistakes.”

Sofia concurs, “From a young age boys and girls can be pushed towards different roles. We get told not to play computer games.” Her recommendation: “You have to be confident, or it’s hard to stick to what you really love.”

Following their Passions

After their URI experiences, both Mariah and Sofia feel encouraged to continue following their passions.

Mariah has applied to begin graduate school, planning to remain in Stein’s lab for a Master of Science in Microbiology. Sofia is still making final decisions about her next steps, but is very interested in pursuing a Master of Audiology degree. Both believe the skills and confidence fostered over a summer in the lab will help them in their future pursuits.

Some lessons learned through the summer?

“It’s okay to try, don’t worry about the wrong way, it’s just your path”, Sofia asserts.

“Have more confidence in yourself,” Mariah concludes.

Thanks to their research experience, both these young women can attest to the fact that very few problems have only one right answer. When life feels like a test of confidence, that understanding will help them both ace it.

If you or someone you know would like to experience the world of cutting-edge FES research, click here to find out more about URI. Applications for the winter 2020 term are open until October 28, 2019.

To learn more about Mariah’s work on Bioconversion of Single-Carbon Effluents into Biofuels and Biofuel Precursors, click here.

You can also watch her Bite Size research:

To learn more about Sofia’s work on Integrated Carbon Capture and (Photo) Reduction Systems: Toward on-line monitoring, sequestration and conversion to useful chemical feedstock, click here.