Art exhibition explores energy futures

Posted on

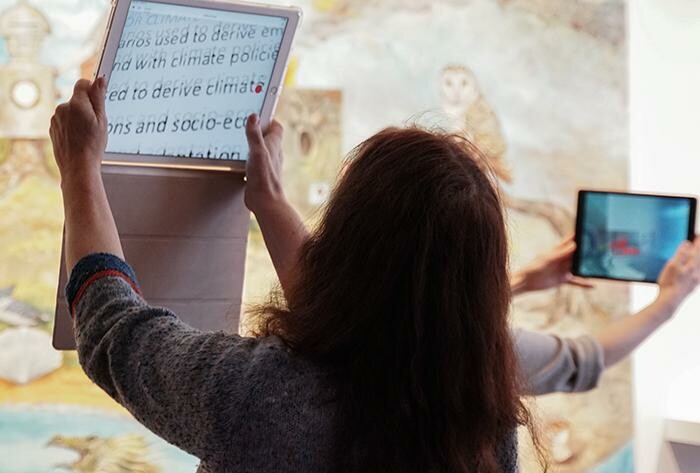

Principal Investigators Natalie Loveless and Sheena Wilson in the FAB Gallery before the opening of the 'Prototypes for Possible Futures' exhibition.

Future Energy Systems art exhibition asks visitors to speculate about an energy future for everyone

On one wall is the Garden of Future Delights –– three paintings that show different potential futures based on alternate simulation models of global environmental change. When you view the paintings through the lens of a specially-calibrated iPad, creatures start climbing off the wall, and you can walk through charts detailing the impacts of climate change according to the United Nation’s Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs).

Further into the exhibition there is a carbon catching library –– venerable library carts stacked with potted cuttings from plants that you can sign out and return using classic borrowing cards. There’s also a card catalogue full of books about plants, permaculture, and carbon capture.

Elsewhere you have the opportunity to listen to Indigenous Knowledge Keepers challenge the values upon which a society is based; to create your own envelopes of seeds to help regenerate the future; to experience the narrative of our planet being for sale; to listen differently to well-known energy narratives; to reflect on whether tools that predict the future can inadvertently shape it; to find the The Lost Garden through a sonic puzzle that imagines the changing sounds of our future energy systems. And on the wall beside each installation you will find questions that prompt reflection and speculation –– that ask you to imagine different energy futures.

All of this is part of the first outing for the artists of Speculative Energy Futures, a project within Future Energy Systems that uses very different tools and techniques than those found in many of the program’s labs. By teaming artists with scientists and engineers, the project is using a proven method to open new conversations about energy transition, breaking down barriers between ideologies and disciplines while making a complex topic accessible to people who might steer away from charts, graphs, and talking points on the nightly news.

Natalie Loveless, the exhibition's co-curator and an Associate Professor in the University of Alberta’s Department of Art and Design, explains: “Our goal is to start breaking down the divisions between academic disciplines, and between academia and the public, so that we can use real research data to provoke speculation about what our energy future can look like to everyone.”

Sheena Wilson, co-curating the project and one of the leads of the Future Energy Systems Energy Humanities theme, adds: “The energy transition gives our society the chance to fundamentally change, and imagining what that looks like means breaking through some of the old conventions of research.”

Until January 11th, 2020 the project’s artists and researchers are hosting their first exhibition, Prototypes for Possible Worlds, at the University of Alberta’s FAB Gallery –– a test flight for their exhibition that will go to the UN climate change conference COP26 in Glasgow next fall.

“Think of this as a pop-up –– a chance for us to learn and refine,” Natalie adds. “It’s the start of a conversation that won’t be easy for anyone.”

Grabbing – and keeping – attention

This is not Natalie’s first time curating an art exhibition that uses science to spur conversations, and she knows that both the artwork and the design of the exhibition are vital to holding visitors’ attention for long enough to make an impact.

“When addressing something as complex and affecting as energy transition, our approach isn’t just to put up an image and ask someone to think about it,” she explains. “The installations and the design of the exhibition have to be interactive, giving people the opportunity for a participatory experience with the topic.”

In 2017, as part of the ImmuneNations project –– an exhibition co-led by researchers from University of Alberta and the University of Ottawa –– Natalie curated an exhibition that was installed at the UNAIDS headquarters in Geneva, with the aim of exploring individuals’ reluctance about proven vaccines.

“In that project our artists teamed with vaccine researchers and public health specialists to explore many pressing issues surrounding global vaccination –– including why, in the face of all the evidence of vaccine safety, people in some quarters still resist immunization,” she explains.

The exhibition included a variety of interactive mixed-media installations, including one that placed visitors in the role of someone battling a fictional disease, Shadowpox, and struggling to use vaccines and herd immunity to prevent a global catastrophe.

“Alison Humphrey and Caitlin Fisher –– who has returned for Prototypes for Possible Worlds –– created that artwork,” Natalie says. “It was very impactful, and positioned in the UNAIDS headquarters it reached people who were thinking about vaccines, but in a very different way.”

Changing the way in which people think about contentious issues is one of the advantages Natalie sees in the use of art. By presenting real research data in ways that stir emotions and invite personal contemplation, she believes that innovative ideas and new conversations can emerge.

“It’s natural for people who are very advanced in a field to frame ideas in the terms of that field –– every problem is a nail if you’re a hammer,” she observes. “I suppose if we stick with that metaphor, we want to help someone who identifies as a hammer to feel free to speculate as if they identified as a tree. To a tree, I doubt every problem would look like a nail!”

But creating art that is interactive, compelling, and true to the data upon which it is based is a challenge –– one that requires reconciling different perspectives about the validity of speculation.

Different kinds of speculation

Through her co-founding of Petrocultures (with Imre Szeman of the Petrocultures Research Institute in 2011) and leadership of Future Energy Systems projects like iDoc and Speculative Energy Futures, Sheena Wilson has pioneered numerous methods for bringing the natural sciences together with the social sciences and the humanities. She knows firsthand that building relationships across traditional divides is not easy.

“The same words can mean very different things in different disciplines, and the only way to overcome those sorts of entrenched understandings is through open dialogue,” she says.

An important first step in that dialogue is to understand the strengths and limitations of each discipline –– whether it is within her own teaching area of Literary and Media Studies, based at Faculté Saint-Jean, or in an engineering or science faculty.

“Speculation is serious business in many fields, including speculative finance and economics,” she explains. “Researchers from the sciences to the fine arts use speculative methods. But if we only talk to people who have the same training we do, it’s easy to assume that our way of speculation is the only valid way –– and to judge other methods by how close they are to our own.”

She points out that modellers working on climate change might rely on numbers in databases and charts, which to them illustrate a certain kind of future.

“But people who aren’t specialists in that field won’t know what those numbers mean, and certainly won’t be able to visualize them. That’s where the fine arts and humanities can come in: finding ways to access these data differently, and help people imagine how the future might work.”

Because their ‘deliverables’ are not quantifiable, Sheena observes that the work of artists might not seem valuable to experts whose research is grounded in experimental results. However, that ability to work in subjective spaces is precisely the strength she believes must be leveraged.

“Most people in the ‘real world’ don’t live in a world governed by experiments –– our reality is subjective, and artists train themselves to function in that subjective reality,” she explains.

She believes that combining artistic expertise with high quality technical research is the key to bringing about meaningful change. The challenge, of course, is in the details.

How to speculate together

As with most exercises in relationship-building, collaborations on artwork come down to trust and respect. Both in her past experience and with Speculative Energy Futures, Natalie has seen how time-consuming the trust-building process can be.

“It’s completely natural: a technical researcher might be very unsure of handing unpublished data to an artist, because they don’t know whether that artist will represent the complexities and nuances of the data accurately,” she says. “This is work that is important to their professional life, and more importantly, to the future of energy. So they feel protective.”

She notes that an artist can be equally wary: “In our current society, the arts seem to be commoditized and undervalued. Someone who has spent years learning how to provoke ideas and engage responses through art might assume that a technical researcher will view them as an illustrator-for-hire –– not a collaborating partner.”

Diplomacy is required to overcome any initial suspicions, beginning with efforts to help each person understand the background, experience, and expertise of the other.

Sheena says: “Natalie and I have developed a feminist approach to this –– collaborative and positive instead of entrenching competition or confrontation. We find common ground –– which is easy when we have a shared goal like energy transition and stopping climate change. We share about how we see ourselves contributing to that goal, we talk about the strengths of the tools at our disposal, the areas in which we need support, and then we start working together.”

Following this philosophy also creates the space needed to consider new ways of knowing, which is especially relevant in the context of energy systems and Indigenous knowledge. In her own installation within Prototypes for Possible Worlds, Sheena and her collaborators Janice Makokis, Patrick Mahon, and Ruth Beer encourage visitors to put on headphones, then listen to and reflect upon Indigenous knowledge presented through oral stories. Connections to Indigenous knowledge and non-colonial ways of knowing are common throughout the exhibition.

“The energy transition gives our society the opportunity to change everything –– not just to swap a solar array for a coal plant, but to think about how we relate to each other in the context of energy,” Sheena observes. “Power doesn’t just mean electricity, it means relationships of control and justice. We can explore many different ways of structuring our society, and that begins with different ways of speculating about energy futures.”

Iterative evolution

Art is not a static thing, and Natalie reiterates that Prototypes for Possible Futures is just the first outing for installations that will evolve over the coming year.

“We want people to come and see this exhibit not just to experience these provocations, but to provoke us too,” she says. “This exhibition isn’t static –– the next time it appears, it might look a little different, or very different. As I said before, this is a conversation.”

That conversation will continue for the team at Speculative Energy Futures as they prepare for COP26 and many events beyond.

“As long as our energy transition continues, we need to be thinking about possible futures,” Sheena concludes. “Art is an important tool in that process, and it is constantly evolving.”

Researchers, Artists, and Co-Applicants who have participated in Prototypes for Possible Worlds: Ruth Beer, Jessie Beier, Sean Caulfield, Evan Davies, Wallace Edwards, Soheila Esfahani, Caitlin Fisher, Joan Greer, Steven Hoffman, Tsēmā Igharas, Satoshi Ikeda, Luke Johnson, Natalie Loveless, Patrick Mahon, Janice Makokis, Kurtis MacAdam, Lisa Moore, Tegan Moore, Sourayan Mookerjea, Mark Simpson, Scott Smallwood, Rachel Snow, Diana Steinheuer, Clarence Whitestone, Sheena Wilson.